National debt is essentially the money a country owes to its creditors. Think of it like a giant version of taking out a loan to fund things you can’t pay for outright, like infrastructure, healthcare, education, or even just keeping the government running during tough times. The creditors? They’re a mix of both local and international players. Here’s how it breaks down:

- Domestic Debt: Money borrowed from within the country, like from banks, pension funds, or citizens who buy government bonds (a fancy way of saying, “You lend the government money, and they promise to pay you back with interest”).

- Foreign Debt: Loans or bonds sold to other countries, international banks, or institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank.

If you see numbers like “trillions of dollars in debt,” it’s often because governments spend more than they earn through taxes and need to borrow to fill the gap. The U.S., for example, owes a lot to domestic investors, foreign countries (China and Japan are big ones), and international institutions.

For developing nations like South Africa, national debt often includes loans from organizations like the IMF or World Bank, sometimes with strings attached, like enforcing policies that don’t always benefit the public.

National debt itself isn’t bad if it’s used wisely, like for long-term growth projects. But when interest payments become unmanageable or borrowing is used just to cover operational costs, it’s like maxing out a credit card to pay for rent, it spirals out f control very quickly. So when countries owe trillions, it’s not just “funny money.” It’s real, and it eventually comes out of the pockets of everyday people like you, me and evereyone we know.

Who Pays National Debt?

The burden of national debt ultimately falls on the citizens of the country, directly or indirectly.

Higher Taxes

Governments repay debt through revenue, and if that’s not enough, taxes go up. This means individuals and businesses bear the brunt, especially in countries with regressive tax systems where the poor pay a larger proportion of their income on consumption taxes like VAT.

Reduced Public Services

To prioritize debt repayments, governments often cut funding for essential services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure. This disproportionately affects lower-income households that rely on these services.

Inflation

If a country prints money to service its debt, it can lead to inflation, where the cost of living rises. While wealthier people may offset this with investments, lower-income families are hit hardest as their wages don’t keep up with price increases.

Stunted Economic Growth

Excessive debt diverts resources from productive investments. A sluggish economy means fewer job opportunities and stagnating wages, affecting everyone but particularly disadvantaging the poor.

Generational Debt

Debt doesn’t disappear. If it’s not managed well, it’s passed down, leaving future generations to pay for today’s borrowing through even higher taxes or reduced opportunities.

In essence, while governments borrow to “invest in the future,” it’s the citizens, particularly those with fewer resources, who often pay the highest price.

While the apartheid system was undeniably horrific, South Africa’s isolation from international financial systems inadvertently insulated the country from the kind of reliance on foreign debt we see today. The sanctions and global boycotts forced South Africa to operate as a highly independent economy, producing much of what it consumed and relying less on external loans or international monetary institutions. This economic insulation also kept our national debt relatively contained, as the government couldn’t easily borrow from foreign sources to fund its operations or growth.

Since the end of apartheid, however, South Africa has re-entered the global economic machine and without the gold backing, seeming “wealth” was created by officials putting pen to paper on global debt traps and the reliance on international organisations funding our economy. Today, much of the country’s national debt is tied to global financial markets, with loans from institutions like the IMF or World Bank and bonds purchased by foreign investors. While this integration has brought opportunities, it has also made the economy incredibly vulnerable to external pressures, such as currency fluctuations, global interest rate hikes and shifts in investor confidence.

This dependency has ballooned national debt to levels that constrain economic growth. Unlike during apartheid, when self-reliance was a necessity, modern South Africa is heavily influenced by the demands and risks of the international financial system. The result is a far more fragile economy, where decisions made in foreign boardrooms often hold more sway than domestic economic policy. The challenge now is finding a way to reduce this dependency while still enabling growth and addressing the country’s pressing social and economic inequalities.

Generational Debt Machine

Adding fuel to the fire is the mindset of new regime, South Africa has become synonymous with corruption and financial mismanagement, significantly contributing to its escalating national debt. While the economic isolation kept the country financially self-reliant, it was an era when gold was our primary export that while the regime handed over the keys it was to the already skuttled ship. While SA’s trade embargos were on the surface lifted the international countries and corporations that had secretly being supporting the local economy through the clandestine gold trade.

The modern government’s entrenchment in global financial systems subsequently created a new debt spiral that was exacerbated by widespread misuse of funds. High-profile scandals, like the blatant looting of COVID-19 relief funds meant to support vulnerable communities during the pandemic, highlight the depth of the problem. Billions were misappropriated or outright stolen, yet the debt incurred to secure these funds still hangs over every citizen in the country. While we payoff the indiscretions of the pandemic this is just a few of the long list

This mismanagement not only damages South Africa’s financial credibility but also undermines trust in its leadership, making it harder to attract ethical investment or secure favorable terms on loans. The consequences of this corruption go beyond tarnishing the country’s reputation, it actually places an immense burden on ordinary South Africans, who bear the cost of repayment through increased taxes and reduced public services. Meanwhile, the funds intended to improve lives disappear into private pockets, leaving the nation with little to show but mounting debt and deepening inequality.

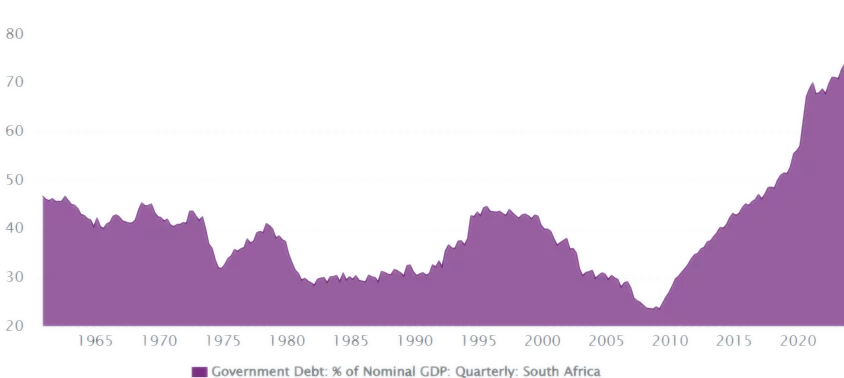

This graph illistrates the alltime high 75.1 % in Sep 2024 but what is interesting is the dip. South Africa’s national debt saw significant reductions under the Mandela and Mbeki administrations, with the debt-to-GDP ratio dropping from 34.6% in 2006 to 28% by 2009. However, debt began to rise sharply during Jacob Zuma and Cyril Ramaphosa’s presidencies, driven by preparations for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, responses to the 2007–2008 financial crisis, and yes the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. So once the corruption took the reigns and figured out how to extract cash the country doesent have the feeding frenzy started, by 2014, the debt-to-GDP ratio had climbed to 43.9% and has continued to climb ever since.

South Africa’s national debt is projected to rise between 2024 and 2029, increasing by a total of $156.8 billion USD which is a staggering further 49.41% growth. After ten consecutive years of climbing debt that we have already endured, the total is expected to hit a new record high of $474.16 billion USD by 2029. This continuous upward trend has been a defining feature of the country’s financial landscape in recent years.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), general government gross debt includes all liabilities that obligate repayment of principal and interest in the future, highlighting that the long-term burden such debt places on the country’s economy.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank play roles in providing financial assistance to nations, but their involvement in countries like South Africa raises questions about their complicity in enabling corruption. These institutions lend money with the stated goals of fostering economic stability, development, and poverty reduction. However, in nations with systemic corruption, these funds are often mismanaged or diverted or as the media presented it “looted” but ultimately leaving South African citizens burdened with repayment.

The IMF and World Bank impose conditions on their loans to ensure proper use, but weak enforcement effectively allows funds to be squandered into the political corruption, benefiting a select few while leaving the broader population to bear the cost. Critics argue that by lending to governments with a history of financial mismanagement, these institutions indirectly support corrupt practices and perpetuate a cycle of debt. With little effort to prosecute offenders or recover stolen funds, taxpayers are unfairly burdened, undermining trust in both international lenders and local governance.

The simplest solution to this issue would be to have independent international adjudicators ensuring that World Bank and IMF funds are used for their intended purposes and directly benefit the projects they were allocated to ESPECIALLY in South Africa. It’s staggering that institutions managing such significant investments would continue lending to governments that have repeatedly demonstrated corruption and financial mismanagement. No private bank or investor would tolerate this level of risk without strict oversight, so why do the IMF and World Bank allow nations to rack up generational debt? By enabling this behavior, they make citizens bear the long-term burden of debts incurred through outright incompetence and dishonesty. It’s time for stricter accountability measures to protect the people these loans are meant to help.